On Human Nature and Anarchy (or Why Zeeshan is Always Wrong, Part I)

One of the many complaints leveled against anarchists and (more commonly) communists is that it looks very good on paper, but it could never work in real life. This is almost always attributed to some shadowy concept known as human nature. Although I do not presume to know anything the natural state of human inclinations, I am relatively certain that faith in the workability of a libertarian socialist community (the idealized end-state envisioned by both anarchists and communists) does not explicitly rely on any specific view of human nature. Furthermore, I would argue that the very concept of a unifying nature for all of humanity is useless both politically and intellectually. Unfortunately, the myth that is imposed upon most radical leftists by those who are not is that we are required to believe that human nature is essentially good. After being told what we must believe, we are then told that this belief is hopelessly naive. This argument can be dismantled three-times over (yippee!).

First of all, if we are to take this particular view of human nature as naive, then it can be easily demonstrated that any other assertion about human nature is also naive. Here are the two useful definitions of naive that I found on dictionary.com:

1. having or showing unaffected simplicity of nature or absence of artificiality; unsophisticated; ingenuous.

2. having or showing a lack of experience, judgment, or information; credulous

Fascinating stuff. Anyways, it seems pretty obvious that people are using the latter connotation of the term when they call anarchists naive. Most people live in a very specific cultural paradigm, which provides a very limited view of a lot of things, including human nature. If one were to make an overarching assumption about the way humans act in a natural state from such a closeted perspective, it would easily qualify as lacking in experience, judgment, and experience. Just because you've been mugged before doesn't mean you know anything more about the human condition than someone who's never been the victim of any crime in their life, and bad things happening to you doesn't automatically make you experienced. The only way to even get a glimpse of human nature would be through a massive cross-section of many different cultures, environments and situations, and even that would be wholly inadequate. Even people in the field which is devoted to the study of people in all different kinds of situations, anthropologists, would be remiss in positing a definite conception of human nature.

The second flaw in the argument stems from the simplicity and vagueness of the assertion. The possibilities of human nature cannot be judged on some linear progression from good to evil. People aren't that simple, and to imply so is ignorant and dangerous. You could at least make the argument that human beings on average tend to act in ways that benefit themselves, but even that is a hollow classification. I believe that this error comes from an incorrect view of human nature itself. Although human beings a by no means born with a tabula rasa, there is definitely an environmental aspect to human behavior, not only in shaping our future actions, but in creating the context for our current actions. To use a particularly absurd example, if it is our nature to collect widgets, can can't really fulfill that nature if widgets don't exist. Environment achieves the dual goal of shaping our mentality and limiting (or perhaps enhancing) our ability to exercise certain instincts. Even this very minor inspection of concepts relating to human nature, it becomes painfully obvious that such a dismissive and simple assessment of human nature falls far short of any practical value.

Finally, and most important of all, this particular view of human nature is not a basic tenet of either anarchism or communism. Let me repeat that. The belief human beings are basically good is not a basic tenet of either anarchism or communism (from here on, I will be discussing only anarchist beliefs). The only belief about human nature that you must subscribe to in order to legitimately describe yourself as an anarchist is to believe that human beings are capable of organizing a non-hierarchical society which is at least as desirable as the current socio-economic paradigm (namely liberal democracy on a national scale and neoliberalism on an international scale). Of course, most anarchists have slightly more ambitious goals than the ones stated above, but those are the bare minimum standards for the most moderate of anarchists.

A corollary of the belief that anarchists have a naive and possibly dangerous view of human nature is that some sort of governing body is required to impose a specific value system on the people (or, in the case of Libertarians and anarcho-Capitalists, some sort of rigid material-incentive program). I will leave out the refutation of the pro-market libertarians' claims for now because it requires a relatively complex argument, and most people are probably already on my side in this matter. However, a pretty handy refutation of this particular argument for government (I must stress that this does not by any means refute all pro-government arguments) is relatively simple.

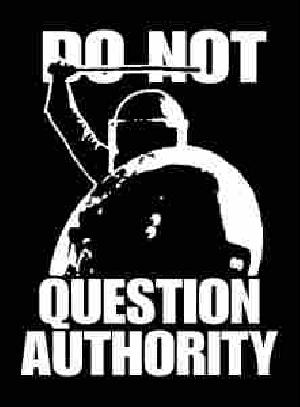

For people who believe that human nature is not essentially good and that people will generally act in their own self-interest when they can get away with it one thing should become quite apparent: that people should have as little power to exercise their will over others as possible. To the stupid eye, this might seem like a de facto endorsement of a massively repressive police state, but a simple thought experiment shows this is not the case. A serial killer with, saw a chain saw and a couple shotguns can, if motivated, kill hundreds of people in his or her lifetime. Now, I obviously don't want this psycho running around chopping off people's heads and whatnot, but his or her danger is minuscule compared to the potential threat of a man or woman will thousands of missiles and an army of trained killing machines at his or her disposal. That, ironically, tends to be the general type of power given to the leaders in countries with a low opinion of human nature. Apparently the person who lied, cheated, bribed, and philandered to get this position is not subject to the laws of nature that govern normal men.

There are three ways to overcome this apparent contradiction. The first involves a pretty skillful utilization of doublethink. The second is by standing by your initial statement about human nature and its implication about the feasibility of an anarchist society, and simply arguing that the aggregate harm done by an entire society of people acting on their nature is greater than the current harm done by the small minority who are currently in charge (plus the damage currently done by the people in society with comparatively fewer freedoms than the elites). I don't really see any logical problem with this argument. I just disagree with the assertion and can probably point to a couple dozen or so examples which seem to contradict it. The final method is to slightly modify one's position on human nature and instead argue that humans are for the most part bad, but that there are a few exceptions who are capable of transcending their nature and acting in purely benevolent ways. Aside from being ridiculously elitist and having a bit too much of a Savior-complex thing going on, there is not really much wrong with this argument, which is essentially an appeal for the installment of some sort of Philosopher King in the vain of Plato's "Republic". I personally believe that some people are more capable than others at certain things, and this must obviously apply to governance. The biggest problem with this proposition is the method used to determine who is fit to have this position of power. I won't go into the details of all the various problems with the different methods of choosing a leader, as I've listed them in previous essays, but I'm sure they are all relatively evident to most people. Another problem with the idea of a Philosophy King is the question of whether the power they are given will corrupt them. Even if you find a supremely benevolent person, it's almost impossible to tell whether or not giving them complete control over a country will cause a negative change in their demeanor and intentions. Of course, presumably the selection process would have some sort of way to figure out if a potential candidate would be corrupted by their newfound power, but this raises even more serious questions about the viability of such a nuanced method of choosing a leader.

First of all, if we are to take this particular view of human nature as naive, then it can be easily demonstrated that any other assertion about human nature is also naive. Here are the two useful definitions of naive that I found on dictionary.com:

1. having or showing unaffected simplicity of nature or absence of artificiality; unsophisticated; ingenuous.

2. having or showing a lack of experience, judgment, or information; credulous

Fascinating stuff. Anyways, it seems pretty obvious that people are using the latter connotation of the term when they call anarchists naive. Most people live in a very specific cultural paradigm, which provides a very limited view of a lot of things, including human nature. If one were to make an overarching assumption about the way humans act in a natural state from such a closeted perspective, it would easily qualify as lacking in experience, judgment, and experience. Just because you've been mugged before doesn't mean you know anything more about the human condition than someone who's never been the victim of any crime in their life, and bad things happening to you doesn't automatically make you experienced. The only way to even get a glimpse of human nature would be through a massive cross-section of many different cultures, environments and situations, and even that would be wholly inadequate. Even people in the field which is devoted to the study of people in all different kinds of situations, anthropologists, would be remiss in positing a definite conception of human nature.

The second flaw in the argument stems from the simplicity and vagueness of the assertion. The possibilities of human nature cannot be judged on some linear progression from good to evil. People aren't that simple, and to imply so is ignorant and dangerous. You could at least make the argument that human beings on average tend to act in ways that benefit themselves, but even that is a hollow classification. I believe that this error comes from an incorrect view of human nature itself. Although human beings a by no means born with a tabula rasa, there is definitely an environmental aspect to human behavior, not only in shaping our future actions, but in creating the context for our current actions. To use a particularly absurd example, if it is our nature to collect widgets, can can't really fulfill that nature if widgets don't exist. Environment achieves the dual goal of shaping our mentality and limiting (or perhaps enhancing) our ability to exercise certain instincts. Even this very minor inspection of concepts relating to human nature, it becomes painfully obvious that such a dismissive and simple assessment of human nature falls far short of any practical value.

Finally, and most important of all, this particular view of human nature is not a basic tenet of either anarchism or communism. Let me repeat that. The belief human beings are basically good is not a basic tenet of either anarchism or communism (from here on, I will be discussing only anarchist beliefs). The only belief about human nature that you must subscribe to in order to legitimately describe yourself as an anarchist is to believe that human beings are capable of organizing a non-hierarchical society which is at least as desirable as the current socio-economic paradigm (namely liberal democracy on a national scale and neoliberalism on an international scale). Of course, most anarchists have slightly more ambitious goals than the ones stated above, but those are the bare minimum standards for the most moderate of anarchists.

A corollary of the belief that anarchists have a naive and possibly dangerous view of human nature is that some sort of governing body is required to impose a specific value system on the people (or, in the case of Libertarians and anarcho-Capitalists, some sort of rigid material-incentive program). I will leave out the refutation of the pro-market libertarians' claims for now because it requires a relatively complex argument, and most people are probably already on my side in this matter. However, a pretty handy refutation of this particular argument for government (I must stress that this does not by any means refute all pro-government arguments) is relatively simple.

For people who believe that human nature is not essentially good and that people will generally act in their own self-interest when they can get away with it one thing should become quite apparent: that people should have as little power to exercise their will over others as possible. To the stupid eye, this might seem like a de facto endorsement of a massively repressive police state, but a simple thought experiment shows this is not the case. A serial killer with, saw a chain saw and a couple shotguns can, if motivated, kill hundreds of people in his or her lifetime. Now, I obviously don't want this psycho running around chopping off people's heads and whatnot, but his or her danger is minuscule compared to the potential threat of a man or woman will thousands of missiles and an army of trained killing machines at his or her disposal. That, ironically, tends to be the general type of power given to the leaders in countries with a low opinion of human nature. Apparently the person who lied, cheated, bribed, and philandered to get this position is not subject to the laws of nature that govern normal men.

There are three ways to overcome this apparent contradiction. The first involves a pretty skillful utilization of doublethink. The second is by standing by your initial statement about human nature and its implication about the feasibility of an anarchist society, and simply arguing that the aggregate harm done by an entire society of people acting on their nature is greater than the current harm done by the small minority who are currently in charge (plus the damage currently done by the people in society with comparatively fewer freedoms than the elites). I don't really see any logical problem with this argument. I just disagree with the assertion and can probably point to a couple dozen or so examples which seem to contradict it. The final method is to slightly modify one's position on human nature and instead argue that humans are for the most part bad, but that there are a few exceptions who are capable of transcending their nature and acting in purely benevolent ways. Aside from being ridiculously elitist and having a bit too much of a Savior-complex thing going on, there is not really much wrong with this argument, which is essentially an appeal for the installment of some sort of Philosopher King in the vain of Plato's "Republic". I personally believe that some people are more capable than others at certain things, and this must obviously apply to governance. The biggest problem with this proposition is the method used to determine who is fit to have this position of power. I won't go into the details of all the various problems with the different methods of choosing a leader, as I've listed them in previous essays, but I'm sure they are all relatively evident to most people. Another problem with the idea of a Philosophy King is the question of whether the power they are given will corrupt them. Even if you find a supremely benevolent person, it's almost impossible to tell whether or not giving them complete control over a country will cause a negative change in their demeanor and intentions. Of course, presumably the selection process would have some sort of way to figure out if a potential candidate would be corrupted by their newfound power, but this raises even more serious questions about the viability of such a nuanced method of choosing a leader.

1 Comments:

I would say that my disagreement with anarchy as a form of society has nothing to do with human nature. Like you, I would argue that there is no "human nature" beyond some extremely basic characteristics - such as the desire to eat, fulfill sexual urges (and even this is variable in the form it takes), etc. My summarized problems with anarchy, in no particular order are (and this is just what comes to mind immediately in the 5 mins im writing this):

In an anarchic society, there is no instituionalized capacity for collective action between individuals. Cooperation is a critical element of human progress. You need cooperation to build roads, deal with the environment, pool resources for the public good, mediate conflict over resources, etc. etc. A government can at least universally levy taxes, and possibly employ them in generally unbiased ways.

Anarchy offers only informal sources of "community action", which - if you take a look at the sectarian, religious, patriotic, nationalistic, and ideological conflicts based on communal action around the world - will constantly threaten individuals and minority communities. If your objection to democracy is that it is "tyranny of the majority", this is the worst possible alternative. The strongest and biggest groups will thrive and progress, and small groups will languish. This is a problem in democracy, but at least groups are forced to arrive at certain peaceful compromises. In reasonably diverse countries, where politically active groups are all small, no one group can dominate all the others and they will be forced to form coalitions and make generally acceptable compromises. There is, of course, the risk of manipulation by and control by a political elite. This is not a problem in anarchy.

This is a risk in democracies of course, but it is not a problem in *all democracies* - and it is somewhat mitigated by the division of power, by federal arrangements, and by constituionally limiting the power of states to infringe on individual rights. If you look at Latin america right now, you can observe the capacity of democracy to break free of manipulation and control by elites - it's not hard. You simply need adequate campaign finance laws, public transparency, popular participation, and institutions for governmental accountability

ok thast's all i can think of right now

Post a Comment

<< Home