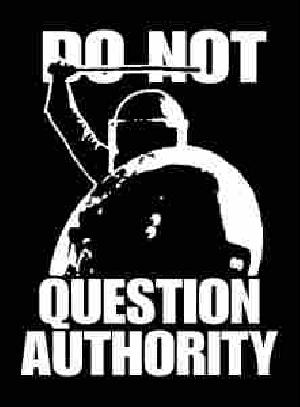

Take THAT, Aditya!

Well, I think freedom of expression is much more psychologically satisfying than intellectual freedom, because you are much more aware of the former. However, that doesn't always mean that is more important. For example, in the Asch Line Studies that you discussed, the people being studied weren't aware at all that their opinions were being manipulated (albeit very subtly). In that sense, they were completely satisfied. However, the manipulation caused them to come up with incorrect conclusions. If their compromised opinion was actually important in some way, the effects could be disastrous. To use an example that has been done to death, if the manipulated information had been the reasons for going to war in Iraq, the people in the study would be in serious trouble.

On the other hand, I think you can argue that intellectual freedom is not very important if you assume that people's opinions don't really matter. Sadly, this is true in many ways. The bulk of public policy is really not determined by the majority of people, but rather an elite few in the upper echelons of society. Yes, the population does contribute to the debate (except for some interesting free trade agreements which are truly terrifying), but the ultimate decisions are made by a handful of people. However, even if most people's opinions are completely inconsequential, the people "in charge" would still require intellectual freedom in order to make informed decisions, assuming they use their knowledge in a way that benefits more than just themselves, which is admittedly a very naive assumption. Furthermore, although most people don't have much say in national and international policies of their government, we still require a certain amount of diversity of opinion to make more "mundane" decisions, such as what car to buy. Also, in "the perfect society" (or at least my vision of it) people would have a lot more say in larger decisions, which would require quite a bit of (untainted) knowledge about a few things.

Also, I'm pretty sure intellectual diversity is essential to any sort of progress. People need to have different opinions in order to devise new solutions to problems, and any measures to stifle diversity can inhibit positive change. It's also possible that lack of intellectual diversity can also inhibit negative change, although that's kind of a complicated issue. My assumption is that in the right situation, a sort of social evolution would prevent that negative "memes" from causing too much damage, although my idea of the right situation is kind of specific. I have a theory about the evolution of states which is somewhat related to this idea that I've probably talked to you about, but have yet to elaborate on. I'll probably do that sometime later. I do realize I use natural selection as a base for a lot of theories altogether too much, but it just makes so much sense.

I would also like to take a moment to point out that encouraging intellectual freedom might not necessarily lead to intellectual diversity. It's very possible that if you provide all the right conditions for freedom of thought (namely strong critical reasoning "training" and free access to a wide variety information) that people will develop a relatively narrow range of opinions about the world. I personally find this highly unlikely, for reasons that I would be happy to elaborate on if anyone actually cares.

A more complicated question is how much a society can actually foster intellectual diversity. If it turns out to be a positive thing to foster intellectual freedom, then it would be an extremely important question to address. However, my assumption is that you can't seriously improve intellectual diversity through structural changes in a society (or maybe through any changes at all), and that all you can do is change the apparatus through which it is shaped. It's ridiculous to get rid of all the distributors of information in the country, which would theoretically prevent any sort of censorship of information, because it would also seriously impede the ability to access information.

On the other hand, leaving the supplying of knowledge to a certain group with its own personal interests is probably not a very wise decision either. For example, the government might suppress information that is critical of the government, a corporation might suppress information that is critical of the corporation or that might not be commercially viable, and I might suppress information that is critical of me or my ideas. There are probably very many pros and cons to each of us being used as arbiters of knowledge, and they would most likely result in populations with a unique outlook on life (presumably one that better suits the main distributer of information's interests). The best solution would probably be to spread the regulation of knowledge to as many entities as possible, and to try to eliminate the motivation to purposely suppress certain works.

On the other hand, I think you can argue that intellectual freedom is not very important if you assume that people's opinions don't really matter. Sadly, this is true in many ways. The bulk of public policy is really not determined by the majority of people, but rather an elite few in the upper echelons of society. Yes, the population does contribute to the debate (except for some interesting free trade agreements which are truly terrifying), but the ultimate decisions are made by a handful of people. However, even if most people's opinions are completely inconsequential, the people "in charge" would still require intellectual freedom in order to make informed decisions, assuming they use their knowledge in a way that benefits more than just themselves, which is admittedly a very naive assumption. Furthermore, although most people don't have much say in national and international policies of their government, we still require a certain amount of diversity of opinion to make more "mundane" decisions, such as what car to buy. Also, in "the perfect society" (or at least my vision of it) people would have a lot more say in larger decisions, which would require quite a bit of (untainted) knowledge about a few things.

Also, I'm pretty sure intellectual diversity is essential to any sort of progress. People need to have different opinions in order to devise new solutions to problems, and any measures to stifle diversity can inhibit positive change. It's also possible that lack of intellectual diversity can also inhibit negative change, although that's kind of a complicated issue. My assumption is that in the right situation, a sort of social evolution would prevent that negative "memes" from causing too much damage, although my idea of the right situation is kind of specific. I have a theory about the evolution of states which is somewhat related to this idea that I've probably talked to you about, but have yet to elaborate on. I'll probably do that sometime later. I do realize I use natural selection as a base for a lot of theories altogether too much, but it just makes so much sense.

I would also like to take a moment to point out that encouraging intellectual freedom might not necessarily lead to intellectual diversity. It's very possible that if you provide all the right conditions for freedom of thought (namely strong critical reasoning "training" and free access to a wide variety information) that people will develop a relatively narrow range of opinions about the world. I personally find this highly unlikely, for reasons that I would be happy to elaborate on if anyone actually cares.

A more complicated question is how much a society can actually foster intellectual diversity. If it turns out to be a positive thing to foster intellectual freedom, then it would be an extremely important question to address. However, my assumption is that you can't seriously improve intellectual diversity through structural changes in a society (or maybe through any changes at all), and that all you can do is change the apparatus through which it is shaped. It's ridiculous to get rid of all the distributors of information in the country, which would theoretically prevent any sort of censorship of information, because it would also seriously impede the ability to access information.

On the other hand, leaving the supplying of knowledge to a certain group with its own personal interests is probably not a very wise decision either. For example, the government might suppress information that is critical of the government, a corporation might suppress information that is critical of the corporation or that might not be commercially viable, and I might suppress information that is critical of me or my ideas. There are probably very many pros and cons to each of us being used as arbiters of knowledge, and they would most likely result in populations with a unique outlook on life (presumably one that better suits the main distributer of information's interests). The best solution would probably be to spread the regulation of knowledge to as many entities as possible, and to try to eliminate the motivation to purposely suppress certain works.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home