In an argument with my dad last night, I noticed two themes that seem to be present in most discussions I have with liberals: A) he believed that cooperation was a good in theory, but in a global society it was at best unfeasible and B) the common man is not very competent. Of course the result of these two views is that many people tend to believe that economic competition (ie people pursuing entirely self-centered goals with little positive collaboration with others) is the best possible option, and that people should not have the right to govern themselves. I find it interesting that most people do not consider the fact that the reason they harbor such undemocratic and anti-egalitarian views is because they live in such an undemocratic and anti-egalitarian society. If you live in a blue world, blue just makes sense to you, and other alternatives (ie green, purple, red, and even *GASP orange) seem really silly in comparison. There's probably some kind of cognitive bias which explains this particular brand of stupidity, but - out of sheer laziness - I'll leave it up to the reader to found out what it is. However it would be inappropriate to attempt to discredit someone's opinion based on their reasons for believing. I believe that's some sort of ad hominem argument. And nobody likes those.

To be honest, I don't really have a handy refutation of my dad's argument against cooperation. While I abhor the Thatcherian dictum that "there is no alternative" I will admit that I don't really have a well thought out alternative in hand. In this issue, most radicals are at a serious disadvantage, because we have to propose something that has never been though of before. Of course the leftists with a penchant for ideological thoughtlessness can quote a few Marxian economists and be done with it, but that hasn't really done much for the movement, so I try to avoid it. My most poignant critique is that, like the argument that the common man is a moron, it is very elitist (if less obviously so). Competition "works", yes, but for whom? I would be very interested to see if the workers in Argentina were impressed with the effects of competition during the economic crisis of 2001. Which interestingly leads to a minor alternative that the people in Argentina had no problem working out. During and since the economic crisis in Argentina, over 15,000 workers have reclaimed the factories they work in. What this means is that they have taken control of management of a particular factory, and then cooperatively and democratically resume production. Most of these factories have continued operating in the face of relatively strong opposition by both business interests and government intervention. Of course the actions of a workplace are completely separate from the greater economic structure governing said workplace, but it's a good start.

On a more theoretical note, one could easily envision a society which operates based on values of cooperation. With even minimal levels of transparency, accountability, communication, recognition, democracy, and self-management, cooperation becomes feasible and definitely desirable. Compare that to the insane concept that "the most wickedest of men [doing] the most wickedest of things" will bring about good for everyone. While this characterization is obviously from someone relatively critical of capitalism (not quite so critical, actually; it's John Maynard Keynes) it's really not that far off from the ever-popular concept of the invisible hand of the market, which is effectively the billions upon billions of exclusively self-interested actions taken by the subjects of capitalism. Furthermore, it would be a profound stretch of the imagination to assume that the "captains of industry", as it were, do not command a great deal more economic power than the average (or common) man. This combined with the fact that these people are generally seen as, at best, moderately unscrupulous, and are admittedly only looking out for themselves, brings us dangerously close to the above quote from our friend Keynes. Coincidentally, Keynes was in large part responsible for a few minor alterations to the robber baron capitalism that he was no doubt attempting to describe (although in my opinion he evidently misspoke and ended up describing all forms of capitalism, from the disturbing laissez faire capitalism of Hong Kong to the euphemistically labeled socialism of Norway). I bring this up because these changes are generally extremely popular among the same liberals who despise democracy and equity. While Keynesianism does seem to stabilize the economy a little and hammer out some of the "kinks" of capitalism, the base problems are still there.

One major problem with attempting to address the above endorsement of cutthroat competition is that it is very rarely fully fleshed out. Most people make some vague reference to human nature and then make a case for capitalism. Of course the case doesn't involve any actual details or supporting evidence. Sometimes people make an offhand comment about the failure of Soviet Russia. Apparently people just support capitalism because they're used to it. I'm not going to address the supposed failure of the USSR other than to say that it wasn't just the absence of capitalism. There were many other factors involved, including what many people saw as the betrayal of the revolution by the Bolsheviks, extreme authoritarianism, and foreign intervention, all of which contributed to many of the problems generally associated with Communism in Russia. Part of the reason that people don't provide many details when they provide their two cents on cooperation versus competition is that it's a highly complex issue. One can provide a myriad of manufactured situations in which one or the other appears to be more beneficial. Even if you were to ignore the inappropriateness of analyzing a completely hypothetical situation and its application to the real world, there is still a problem. One isolated event of cooperation or competition means nothing when you discuss the fact that the economy is made up of perhaps trillions of these "isolated" situations over the course of years and years. Furthermore, capitalism isn't just the sum of all of these interactions. It also consists of the structure governing the economic interactions between individuals within a specific society. This allows for people to act in conjunction with each other, or act against each other's interests (although the latter is encouraged pretty heavily). Ultimately, the only way to test the theory that competition is more compatible with human nature or healthier for society is intense experimental testing, including study of human psychology and organic discovery of alternative economic structures. One proposed system that I have begun to embrace is participatory economics. I won't get into the particulars here, but here's a link to some information about it.

Disgust with the common man is a lot easier to discuss. Of course most people disguise this sentiment by claiming that human nature is evil (as opposed to awesome) and use that to justify a relatively hostile attitude towards democracy. Very few people go on to mention the accompanying thought: "except for me". Still fewer voice the other obvious corollary: "and those of my class". In this regard I'm pleased that my dad was so honest in his assessment. Although it's a very elitist and self-important thing to say, it makes the conversation a lot more open.

As somewhat of a warm-up, I'm going to address my most serious problems with the assertion that human nature is somehow evil, or at the very least incompatible with social justice. First of all, that is a ridiculously presumptuous statement to make. To see all these people making such absolute claims about human nature, you'd think about half the population of this country not only had simultaneous PhDs in Biology (with a focus on evolution), Anthropology, Psychology, Cognitive Science, Economics, Game Theory, and Philosophy but also access to a country-sized laboratory with a multi-trillion dollar grant and permission to use any and all human subjects as virtual lab rats in billions upon billions of unique and highly controlled experiments. I mean Jesus, learn some humility and realize the extremely complex nature of the concept you're attempting to sum up in one simple sentence. Of course, it's a bit hypocritical of me to chide people for not being humble enough, especially in intellectual matters, but the point is that these people are making extremely authoritative statements about something that they know very little about. I actually think it's sufficient to refute any theory about human nature with an argument along these lines, but even if one actually were to accept such a ridiculous claim, it's very easy to break apart the conclusions they come to based on this assumption. Of course one could always make a ridiculously specific claim about human nature such as: "human nature operates in such a way that the current political and economic paradigm in the United States, coordinated with similar such states in countries throughout the world, for and by the powers that be, such as corporate and political leaders in the West, in pseudo-collaboration with leaders in the global South is the best possible state of global affairs", but even people that presume to know intimately about human nature would agree that at a certain point one must acknowledge that some degree of vagueness is necessary in describing human nature.

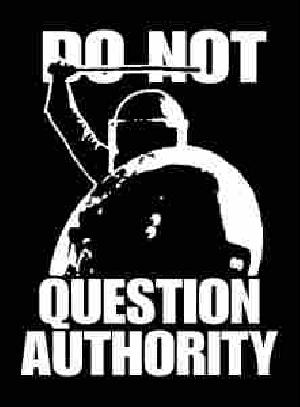

If we disregard the crazed ramblings of self-important whack jobs (myself excluded), then we can focus on a general idea about human nature, such as human beings are general self-interested, desire instant gratification, tend to be irrational (especially during important and stressful times), and are stupid and lazy. My first statement when confronted with such a bleak view of other people (because we have to admit that no one actually thinks such base characterizations actually apply to themselves) is "Good God, and you want to give a random one of the depraved individuals that you just described excessive power over you?" Which I think is actually a better argument than most people would admit. If I actually believed this about people, assuming I was somehow prevented from living in a shack in Antarctica and amassing as powerful an arsenal as humanly possible to defend me against the inevitable invading hoards of Zombies that are the human race, I would have a serious problem with consenting to giving a small percentage of the population control of a badge and a gun, an even smaller percentage of population control of the bulk of the economy, a few thousand absolute control over the legal system, and a couple dozen people power over the nukes. Instead, I'd be spending a lot of my time attempting to develop an alternative which prevents anyone from being able to get too much power over me. Nobody explains why the result of their dim view of human nature results in a politics that effectively rounds up the worst, most self-interested of the lot, and makes them jump through random hoops so they can get elected and then formulate the laws that are enforced by more of the worst of the lot at the point of a gun, or an economy that actually encourages the worst of human nature. More importantly, people who make this argument are nonplussed by such refutations, because they're not actually making this argument. They're actually making the argument that my dad was making, but since that argument makes most people look like arrogant assholes, they're afraid to admit it, especially to an angry and rather large anarchist with a propensity towards particularly animated debates.

As far as I can tell, the argument - especially when used to justify a relatively authoritarian political system and a hierarchical economy - is that the speaker, and the people s/he general associates with are generally intelligent, compassionate, thoughtful people, who are capable of making informed decisions about personal and political affairs. In general, they deserve political freedom and are completely suited to self-management, as well as economic autonomy. The common man, however, can't even be counted on to tie his shoes right. Nobody every quite states exactly who the common man is, but there's a very strong implication that the bulk of these people come from the "lower classes". Unfortunately, the bulk of my interactions are with people a half step away from the ruling class, so I don't know all that much about how people in the middle and lower class justify this position. Either way, it's pretty stupid to assume that you and the people you associate with are somehow better than everyone else. Furthermore, if you belong to the upper class, I would bet dollars to donuts that it's not because you pulled yourself up from your bootstraps. Nonetheless, many people in this position develop some bizarre sense of entitlement, which can feed into the above belief that you're better than everyone else. Since you most likely did nothing to get yourself into this prestigious tax bracket, there's no reason for this sense of superiority. Hell, even if you did go from rags to riches, that just means you're a combination of lucky and good at making money. That hardly makes you a superior breed of human, especially with regard to socio-political decisions. In fact, being part of the upper class is going to guarantee at least some degree of separation from the bulk of the population, which makes your opinions generally less important than those of the middle and lower class.

If you have made some argument along the lines of the idea that human nature is incompatible with social justice, then try to be honest with yourself. If you meant that "other people’s" nature is incompatible with social justice, while you and your friends and family are squeaky clean, trying to think about how deranged, elitist, and "convenient" that idea is. Most likely there's no real evidence to this assertion. If you think all people are evil, then you're probably just a very screwed up person, and God help you.

By the way, I'm aware that this article is relatively unpolished, but I just came back to it after weeks of inactivity, and I didn't really feel motivated to make the necessary changes to it or completely rewrite it (which is probably what I should have done). Also, due to Zeeshan's aggressive posturing, I've decided to launch a preemptive strike, and so I kind of hastily finished this essay. Either way, it's probably a good idea to start writing again. After two months of not writing a thing, I'm probably gonna have to ease back in pretty slowly.