I am an Idealist

Yeah, that's right, I'm and idealist. I don't really see why that has to be a dirty word. In the most bare-bones way, I would define an idealist (aside from the philosophical considerations) as someone who has some sort of conception of a perfect world, and would like to see it be that way. Most rational human beings would consider that to be a prerequisite for someone to be a moral human being (I know that's a kind of absolutist generalization, but I assume most would agree with the general sentiment). The one exception to the previous conclusion is the people whose ideals completely (or mostly) match the practices of the current world order.

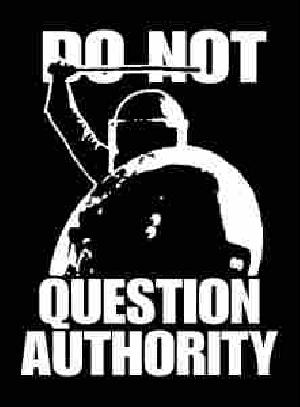

I personally believe that the pejorative classification of idealist more accurately describes these people. Many people simply consider idealist to be a rough synonym for naive, and absolute faith in market economics and authoritarian politics in the face of overwhelming global poverty, racism, and lack of economic stability seems pretty naive. Furthermore, the believe that we are very close to achieving the ideal society is a patently naive (as well as disturbingly apocalyptic) idea. This idea is strongly associated with revolutionaries of all stripes, but we can't forget that almost all non-revolutionaries have committed the even more egregious error of assuming that we have already achieved ideal society. They may both be wrong, but it can be argued that the acts of the (perhaps misguided) revolutionaries is in some small way contributing to social progress, while the others are creating stagnation.

At this point I'd like to specify what I mean by revolutionary. The terms I've been using are kind of misnomers, but it's a lot simpler. Anyways, in this context I consider revolutionaries to be people who are actively fighting for a revolution (violent or non-violent) which they believe to be imminent. I personally would not consider myself a revolutionary in this sense. However I do not identify with the vast majority of non-revolutionaries who have pretty much accepted the status quo (the ones who have committed the egregious error). I belong to the minority of non-reformist and non-revolutionary radicals who believe that the ideal society will not be achieved in "One Big Revolution" and may even doubt that a better society may not even be possible (obviously a perfect society is almost by definition impossible, but most believe that there are some minimum standards that are achievable).

The final definition of idealist which I will address comes from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, and provides a happy middle-ground between my initial definition and the excessively negative one. They say that and idealist is "one guided by ideals; especially : one that places ideals before practical considerations". I accept this definition wholeheartedly, provided I can elaborate on what being "practical" is. "Practical" cannot exist in a vacuum. In order for a means to be considered practical, you must have some sort of end in mind. Now, in achieving the current goals of modern society- namely political expediancy, market efficiency, corporate power, massive incarceration, and generally supporting the system- my views are very impractical. For example (although I do not actually support this) people who vote for third parties are generally seen as wasting their vote, more or less because it's impractical. Therefore, in a coutry where the two mainstream parties are virtually indistinguishable, the only possibility for change "ironically" becomes impractical. Change is impractical. However, if you decide on some slightly more humanitarian goals - low poverty and starvation rates, high literacy rates, economic equity, intellectual freedom, etc. - my beliefs become decidedly practical.

So in that sense, the majority of society is idealistic, holding the ideals of the Constitution, Bill of Rights, Declaration of Independence, etc. above the practical considerations of human life.

I personally believe that the pejorative classification of idealist more accurately describes these people. Many people simply consider idealist to be a rough synonym for naive, and absolute faith in market economics and authoritarian politics in the face of overwhelming global poverty, racism, and lack of economic stability seems pretty naive. Furthermore, the believe that we are very close to achieving the ideal society is a patently naive (as well as disturbingly apocalyptic) idea. This idea is strongly associated with revolutionaries of all stripes, but we can't forget that almost all non-revolutionaries have committed the even more egregious error of assuming that we have already achieved ideal society. They may both be wrong, but it can be argued that the acts of the (perhaps misguided) revolutionaries is in some small way contributing to social progress, while the others are creating stagnation.

At this point I'd like to specify what I mean by revolutionary. The terms I've been using are kind of misnomers, but it's a lot simpler. Anyways, in this context I consider revolutionaries to be people who are actively fighting for a revolution (violent or non-violent) which they believe to be imminent. I personally would not consider myself a revolutionary in this sense. However I do not identify with the vast majority of non-revolutionaries who have pretty much accepted the status quo (the ones who have committed the egregious error). I belong to the minority of non-reformist and non-revolutionary radicals who believe that the ideal society will not be achieved in "One Big Revolution" and may even doubt that a better society may not even be possible (obviously a perfect society is almost by definition impossible, but most believe that there are some minimum standards that are achievable).

The final definition of idealist which I will address comes from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, and provides a happy middle-ground between my initial definition and the excessively negative one. They say that and idealist is "one guided by ideals; especially : one that places ideals before practical considerations". I accept this definition wholeheartedly, provided I can elaborate on what being "practical" is. "Practical" cannot exist in a vacuum. In order for a means to be considered practical, you must have some sort of end in mind. Now, in achieving the current goals of modern society- namely political expediancy, market efficiency, corporate power, massive incarceration, and generally supporting the system- my views are very impractical. For example (although I do not actually support this) people who vote for third parties are generally seen as wasting their vote, more or less because it's impractical. Therefore, in a coutry where the two mainstream parties are virtually indistinguishable, the only possibility for change "ironically" becomes impractical. Change is impractical. However, if you decide on some slightly more humanitarian goals - low poverty and starvation rates, high literacy rates, economic equity, intellectual freedom, etc. - my beliefs become decidedly practical.

So in that sense, the majority of society is idealistic, holding the ideals of the Constitution, Bill of Rights, Declaration of Independence, etc. above the practical considerations of human life.